For many years, despite repeated requests, a South African bank has been sending me bank statements.

The thing is that I don’t live in South Africa, have never visited, nor banked there. But I do have a particularly “good” email address that gets a lot of misdirected emails… I usually don’t read them, but this week I did, as I replied for the latest attempt of “please stop”.

The email included a PDF statement, password protected with the South African ID number of the customer. I suspect that protection is why the service centre seem so unbothered by the repeated requests to stop this information.

A few years back, I got very embedded in PII/GDPR. We were designing a data warehouse setup that allowed analysis of user activity, while protecting privacy, and enabling easier compliance with GDPR deletion requests. There was discussion about the feasibility of SHA2 hash reversal… and we took a lot of time to communicate the infeasibility with the legal team.

So this week, I started to wonder: If I were a bad actor (which I am not), could I feasibly crack this ID with some Python?

What’s the challenge?

There are three sets to consider in this:

- The Absolute Keyspace: without any knowledge of the identifiers, the number of combinations?

- The Available Keyspace: if the ID has constraints, how many valid combinations are there?

- The Effective Keyspace: if we know anything more, how many combinations are applicable?

A good security identifier should make discerning the differences between these difficult: it should involve a reasonable amount of calculation before it becomes obvious that an ID is valid, and correct.

What do we know?

South African ID Numbers are 13 decimal digits.

A single decimal can be 0-9, ten in total, and so each digit has a a cardinality of 10.

(Cardinality being the maths word for ‘number of choices’ in a set)

We can use this information to calculate the absolute keyspace:

Since this work was derived in a Jupyter notebook, I’ll also include some python as we go along…

Python Code for absolute keyspace

number_of_digits = 13

keyspace_absolute = 10 ** number_of_digits

print(f"Number of combinations: {keyspace_absolute:,}")Number of combinations: 10,000,000,000,000Is this feasible?

So without knowing anything about the ID, there are 10 trillion combinations to check.

Python can attempt to open a PDF with a password around 150 times per second. This would be our basic implementation.

More specialised tools like John the Ripper raise that rate 4,500 per second, that’s around 30 times faster.

We’ll put these into a summary function, as we’ll be calling this a few times.

Python for Summary Function

test_rate_slow = 150

test_rate_fast = 4500

def summary_to_brute_force(combinations):

hours_to_test_slow = (combinations / test_rate_slow) / 60 / 60

hours_to_test_fast = (combinations / test_rate_fast) / 60 / 60

return f"At slow rate: {hours_to_test_slow:,.2f} hours, or: {hours_to_test_slow / 24:,.2f} days" + \

f"\nAt optimised: {hours_to_test_fast:,.2f} hours, or: {hours_to_test_fast / 24:,.3f} days" print(summary_to_brute_force(keyspace_absolute))

At slow rate: 18,518,518.52 hours, or: 771,604.94 days

At optimised: 617,283.95 hours, or: 25,720.165 daysAt this stage, it would not be worth the cost to brute-force this.

The information in the ID, or the document, is not valuable enough.

Scoping the “Available Keyspace”

The South African ID format is described here and this OECD PDF.

The format is YYMMDDSSSSCAZ:

YYMMDDis the date of birthSSSSseparating people born on the same day- Female entries start

0-4, males entries start5-9

- Female entries start

Crepresents citizenship statusAwas previously used to represent race, but is now unspecifiedZis a checksum digit, using the Luhn algorithm

How does this help us?

The Z check digit reduces the key space by a factor of 10: we “only” have to brute-force for the first 12 digits, and calculate the 13th.

Since A is unspecified, we will leave its cardinality unchanged at 10.

The C citizenship status can be 0, 1, or 2. This digit now has cardinality of 3 instead of 10.

Dates

The YYMMDD digits are dates, these have constraints:

- Years are from 00-99

- Months are from 01-12

- Days are from 01-31

If we just consider those digits individually, we can calculate the cardinality like this:

But that’s going to consider many impossible days: month 19 doesn’t exist, nor does day 35.

So we could just consider these 6 digits as a combined date field, and get a more useful answer:

(Yes, I am ignoring leap-years in this calculation… they’re not material to this calculation)

Our new understanding of the ID number format comes together, and we can compare the Absolute with the Available keyspaces:

So even without any knowledge of the target, only 0.1095% of the original key space needs to be searched.

Python for Available keyspace

cardinality_of_birthdays = 100 * 365 # we're ignoring leap years

cardinality_of_serial_numbers = 10000

cardinality_of_citizenship_states = 3

cardinality_of_the_a_digit = 10

keyspace_available = cardinality_of_birthdays * cardinality_of_serial_numbers * cardinality_of_citizenship_states * cardinality_of_the_a_digit

print(f"Number of valid ID numbers: {keyspace_available:,}")

print(summary_to_brute_force(keyspace_available))

Number of valid ID numbers: 10,950,000,000

At slow rate: 20,277.78 hours, or: 844.91 days

At optimised: 675.93 hours, or: 28.164 daysOne month with optimised checking could be feasible, especially if you rented some machines… but can we do better?

What’s the Effective Keyspace?

Revisiting the email, it contains some info I’ve ignored until now:

- The last 4 digits of the ID as verification

- The recipient is addressed as ‘Mr Customer’

Going back to the format YYMMDDSSSSCAZ.

We know the values for C & A, so those now have cardinality of 1.

C‘only’ had a cardinality of 3, so that’s excludes 67% of possibilitiesAhad a cardinality of 10, so that excludes of 90% of possibilities

These combine however, so the remaining amount from knowing C & A is: katex is not defined

Let’s reconsider the SSSS block: which we’ll refer to as S1, S2, S3, S4.

- Since our ID is male we know that the

S1must be 5/6/7/8/9, so cardinality of that digit is now 5 - We know

S4, so it has cardinality of 1

Again these combine, so the total remaining is: katex is not defined

Checking in the formula again:

We’re now down to 18.25 million possible keys to check.

Python for effective keyspace

cardinality_of_birthdays = 100 * 365 # ignoring leap years for now

cardinality_of_serial_numbers = 500

cardinality_of_citizenship_states = 1

cardinality_of_the_a_digit = 1

total_number_of_email_matching_combinations = cardinality_of_birthdays * cardinality_of_serial_numbers * cardinality_of_citizenship_states * cardinality_of_the_a_digit

excluded_by_using_email_information = keyspace_available - total_number_of_email_matching_combinations

print(f"Number of numbers matching email: {total_number_of_email_matching_combinations:,}")

print(summary_to_brute_force(total_number_of_email_matching_combinations))Number of numbers matching email: 18,250,000

At slow rate: 33.80 hours, or: 1.41 days

At optimised: 1.13 hours, or: 0.047 daysEven the naive, 1.41 days is really starting to look feasible, and with John the Ripper, we’re already doing it in little over an hour.

But what about the check digit?

Earlier we ignored the check number, since we can calculate it… but we were supplied it in the email.

We can use it to see if the ID is a potential match, and only check matching ones against the file.

Luhn format checkdigits use simple modulo 10 arithmetic.

This means only 10% of the generated IDs will be checked against the PDF password.

Python for checksum validated keyspace

using_checkdigit_exclusion = total_number_of_email_matching_combinations / 10

print(f"Entries matching email check digit: {using_checkdigit_exclusion:,.0f}")

print(summary_to_brute_force(using_checkdigit_exclusion))Entries matching email check digit: 1,825,000

At slow rate: 3.38 hours, or: 0.14 days

At optimised: 0.11 hours, or: 0.005 daysOur ‘effective’ keyspace is now 1,825,000 entries.

So even with a naive implementation just in Python, we can do it in less than a day.

Age scoping

A friend pointed out that searching all ages between 0-100 is a bit pointless, so we could change that to be a range of 18-70?

Because the birthday field covers 100 years cleanly, we calculate the number of years we want to test.

However, given the effective keyspace we’re already down to, the impact of age reduction feels less useful in this scenario, if you had less information this reduction could be more useful.

Python for age reduced keyspace

min_age = 18

maximum_age = 70

age_range = maximum_age - min_age

percentage_of_people_in_age_range = age_range / 100

total_number_in_age_range = using_checkdigit_exclusion * percentage_of_people_in_age_range

print(f"Number in valid age range: {total_number_in_age_range:,}")

print(summary_to_brute_force(total_number_in_age_range))

Number in valid age range: 949,000.0

At slow rate: 1.76 hours, or: 0.07 days

At optimised: 0.06 hours, or: 0.002 daysIn summary

From an absolute key space of 11,000,000,000,000, we’ve excluded over 99.99999% of the possible numbers, and have only 949,000 to check against the file.

Python to generate table

import pandas as pd

data = [

[ keyspace_absolute, 100],

[ keyspace_available, 100 * keyspace_available / keyspace_absolute],

[ total_number_of_email_matching_combinations, 100 * total_number_of_email_matching_combinations / keyspace_absolute],

[ using_checkdigit_exclusion, 100 * using_checkdigit_exclusion / keyspace_absolute],

[ total_number_in_age_range, 100 * total_number_in_age_range / keyspace_absolute],

]

df = pd.DataFrame(data, columns=["Count", "Percentage of Total"], index=["Absolute Keyspace", "Available Keyspace", "Email Keyspace", "Using Email checkdigit", "Limiting by Age"])

brute_force_label = f"Hours @ {test_rate_slow}/s"

brute_force_faster_label = f"Hours @ {test_rate_fast:,}/s"

df[brute_force_label] = df["Count"] / test_rate_slow / 60 / 60

df[brute_force_faster_label] = df["Count"] / test_rate_fast / 60 / 60

df.style.set_properties(**{'font-family': "Menlo, Consolas, Monospace"}) \

.format(subset=["Count"], thousands=",", precision=0) \

.format('{:.6f} %', subset=["Percentage of Total"]) \

.format(thousands=",", precision=1, subset=[brute_force_label, brute_force_faster_label])

| Set of potential ID Numbers | Size of set | Percentage of Absolute | Hours @ 150/s | Hours @ 4,500/s |

| Absolute Keyspace | 10,000,000,000,000 | 100.000000% | 18,518,518.5 | 617,284.0 |

| Available Keyspace | 10,950,000,000 | 0.109500% | 20,277.8 | 675.9 |

| Email Keyspace | 18,250,000 | 0.000182% | 33.8 | 1.1 |

| Using Email Checkdigit | 1,825,000 | 0.000018% | 3.4 | 0.1 |

| Limiting by Age | 949,000 | 0.000009% | 1.8 | 0.1 |

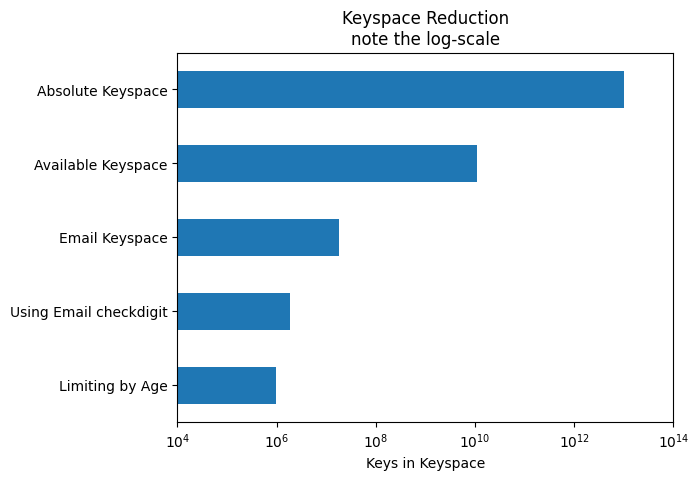

Visualisation

Graphing this is really hard, differences in scale make it really difficult to communicate.

Since I’m not a data-vis genius, this uses a log-scale.

Python to generate Graph

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

data = df['Count'][::-1]

data.plot(kind='barh', logx=True, title="Keyspace Reduction\nnote the log-scale",ax=ax)

vals = ax.get_xticks()

ax.set_xticks(ax.get_xticks()[::2])

ax.set_xlabel("Keys in Keyspace")

Conclusions

This analysis shows that in common with recent attacks on the Tetra encryption system , if you’re not using all of the absolute keyspace, your protection is far weaker than may appear from a big number.

These national/structured IDs do not make good secrets: the structure inherently reduces the size of the effective keyspace, and makes it very easy to exclude ranges of people (by age or gender).

While phishing is a problem, and emails need to be/appear authentic – we need to use mechanisms to achieve this at the email level: SPF, DKIM, DMARC, BIMI. While imperfect, these are far better than including information directly related to the ID/information being protected.

In this scenario even with a naive implementations, it would be entirely feasible to brute-force this particular email/pdf combination, which would expose customer information.

Now I don’t know how valuable that information in the statement is, but I wonder if it be used as part of a social engineering attack?

A plea to companies: If I message asking you to stop send me statements, maybe stop?